(updated May 2024)

Global survey shows simple solutions to common web accessibility errors

Simple things make the biggest improvements in the world of web content accessibility.

Each year, the WebAIM Million report reveals the most common content accessibility errors on the world’s top websites. The comprehensive snapshot of web accessibility shows slight improvements as web owners gain a better understanding of how best to serve all site visitors. But it also reveals that the same accessibility errors are turning since the survey began.

Most of these common errors don’t require big technical fixes. By building simple processes into web content creation, you can make a tremendous difference for people with disability who want to access your site.

What is the WebAIM Million?

The WebAIM Million is an accessibility analysis of the world’s 1,000,000 most popular home pages. Produced by American web accessibility non-profit organisation WebAIM, it reports on web accessibility barriers and instances where sites fail international accessibility guidelines.

The 2024 study found an average of 56.8 accessibility errors on each of the million home pages analysed. It reported that the same error issues appear every year led by low-contrast text, missing image alt text, missing form labels and empty or ambiguous links.

The study uses a detection tool to pick up home page errors. But it can’t detect all errors. This means the number of actual accessibility issues is likely to be greater than reported.

Don’t lose customers to poor web accessibility

Common reasons people give for not making their websites more accessible include:

- it’s too difficult

- I don’t have time

- I don’t know any disabled people

- we don’t have disabled people using our site

- it takes too long

- I don’t have the skills.

Given at least 1 in 6 Australians identify as having disability, it is likely that you do in fact know someone who would appreciate better web accessibility.

There are also those who do not identify as disabled, and those who experience temporary or situational disability. Perhaps a broken arm makes it difficult to use a mouse, or a noisy environment presents hearing challenges.

Making content accessible is why the internet exists

Web accessibility is about designing and developing websites to make content available to anyone who wants to access it.

International standards for web content accessibility are developed with individuals and organisations around the world and published by the Web Accessibility Initiative of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). They are known as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

In Australia, web accessibility is embedded in our Disability Discrimination Act, and Australian Government agencies are required to meet WCAG 2.2 level AA as a minimum. If you work with government agencies, you might also be expected to comply with WCAG standards.

Beyond government or legal requirements, it just makes sense to ensure your website is as accessible as it could be. Accessibility is not only a human right, it also means more potential clients, volunteers and donors can get the information they need to do business or interact with you.

Simple accessibility solutions to big accessibility problems

Building a fully accessible website begins in the planning and development stages. But that doesn’t mean you can’t improve your existing website. Many of these fixes require little more than time. You can start today by building accessibility into your everyday content processes.

- Add alt text every time you upload an image to your site.

- Use an online tool to check the contrast of your text colour against the background.

- Describe links so users know where they lead.

- Get familiar with heading tags to structure your content so screen readers can make sense of it.

- Ditch flashy graphics and keep things simple to avoid complexity errors.

A communication specialist who understands web content accessibility can do this for you, or help set up your processes. Improving accessibility is about improving the user experience. And that’s good for all your site’s visitors.

According to the WebAIM Million report, ‘addressing just these few types of issues would significantly improve accessibility across the web‘.

‘Addressing just these few types of issues would significantly improve accessibility across the web.’

WebAIM Million Report, 2024

Complex web pages add to accessibility errors

Across the million home pages analysed, the study picked up 56,791,260 distinct accessibility errors. This was just 13.6% more than in 2023.

In total, 95.9% of home pages had WCAG failures — a slight improvement on the 96.3% with errors in 2023. Among these, 22.2% of pages had five or fewer errors and 31.2% had 10 or fewer.

Over the same time, however, home page complexity increased. Complexity relates to the number of elements on the page, such as images, headings, buttons, menus, tables, lists, forms and links.

Home page complexity is an increasing trend, growing by 50% in the past five years. The report says users with disability can now expect to encounter errors on one in every 21 home page elements.

Top web content accessibility fails

The top home page accessibility errors picked up by the analysis are:

- low contrast text on 81% of home pages

- missing alt text on 54.5% of home pages

- missing form input labels on 48.6% of home pages

- empty links on 44.6% of home pages.

Do any of these content accessibility errors appear on your website?

Colour choices matter for accessible web content

How often do you check colour combinations for accessibility? The WebAIM Million report found 81% of errors on popular home pages related to low-contrast text.

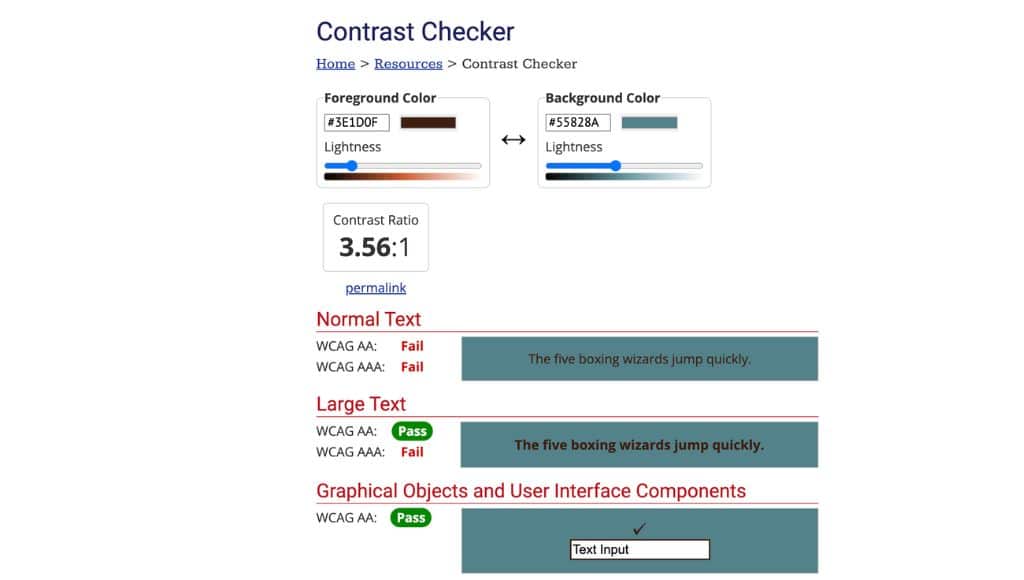

This refers to how well a text colour stands out against its background. To comply with the WCAG AA standards, colour contrast ratios for text against background should be 4.5:1 for 12pt text and 3:1 for larger text (14pt bold or 18pt regular). This ratio measures the difference in the perceived brightness between the two colours.

Tempted to dismiss colour contrast recommendations? Perhaps you think vision-impaired people don’t use your site.

Globally, one in 12 males and one in 200 women experience some form of colour blindness. Certain colour combinations create particular problems for people with colour blindness, such as red/green and blue/yellow.

Various free online tools let you test the contrast ratios of your colour combinations. Many of these help you adjust the colours so they pass accessibility standards. WebAIM has a contrast checker on its site, while Vision Australia also has a colour contrast analyser.

Free simulation tools are available that apply a filter to your web pages so you can visualise how they might look to a colour-blind user. Some examples are the No Coffee Vision Simulator extension on Firefox or Colorblindly on Chrome.

Often, an organisations hits colour contrast hurdles if their brand design process did not consider accessibility from the outset. These organisations may end up with brand colour palettes that fail the accessibility test when used to produce web or printed content. If you are developing a new brand or considering a rebrand, include accessible colour combinations in the planning and design process to save you headaches down the track.

While logos and other decorative or artistic elements don’t need to meet colour contrast requirements, consider why they are on the page. If it is for visitors to perceive them, they might as well be as accessible as possible along with the rest of your content.

It is also important not to rely on colour alone to convey information. For example, there is a trend towards links that appear with different coloured, or bolded, text but no underline. If visitors can’t perceive the different colour, they have no way of knowing the text is a link.

Alt text makes images accessible

Websites are incorporating more images and graphical elements, with the WebAIM Million finding a 28% increase over the past year.

Images and graphics are a great way to break up text, convey information in different ways, and make a page look more appealing. But problems arise when the images do not have alternative text.

Alternative text, or alt text, is important because it:

- enables screen readers to announce details of the content for people who have visual or cognitive impairments

- describes what should be there if an image doesn’t load

- supports SEO by helping search engines understand and rank page content.

The report found more than one in five home page images had missing alt text.

Of those that had alt text, 14.6% were classified as ‘repetitive or questionable’. This might be unhelpful alt text such as ‘image’, ‘graphic’ or an indecipherable file name. Repetitive alt text occurs when it duplicates text already on the page near the image.

It’s easy to make images accessible on your website.

You already know how to compress and resize an image so it won’t slow down your site load.

You know to name the image file so it includes the SEO keyword for the page it will appear on.

Now you can add alt text to your image optimisation checklist.

It takes less than a minute to fill in the alt text box every time you upload a new image to your site.

Just remember to keep it brief but helpful. You don’t need to start with ‘image of’ or ‘picture of’ because the screen reader alerts the user to what an element is. Describe its purpose on the page. If the image wasn’t there, what text would you need to replace it? Include — but don’t repeat — extra image description in a caption.

Once you’re in the flow of optimising all new images, set aside a little time each week to add alt text to the existing images on your site.

Empty or ambiguous links cause navigation problems

Screen readers let users scan a page, providing a list of links to select from. When link text or code does not make clear its purpose or where it leads, it is unhelpful to the site visitor.

The WebAIM MIllion report found about half of the surveyed home pages had empty links. Empty links have no, or incomplete, functional information to explain where they lead. The most common types of empty links include links behind images and icons, and links that are accidentally deleted while editing content online.

Ambiguous links refer to those that provide no, or inadequate, description. Link text such as ‘read more’, ‘click here’, or ‘see details’ are repetitive and unhelpful. So-called naked links, which use the URL itself as the anchor text, are also inaccessible as they don’t always provide sufficient information about the link’s purpose.

Aside from supporting assistive technologies, descriptive links help all site visitors. Eye tracking technology shows humans scan pages for clickable items; a process known as ‘information foraging’. Vague wording on links means your site’s visitors need to take more time to figure out what a link is for, which can lead to frustration.

Again, it’s a simple fix. Writing descriptive links that clearly describe their purpose will not only improve your site content’s accessibility, it also makes for a more interesting and helpful overall user experience.

When adding links to images, describe the destination within the image alt text.

If descriptive links are not possible, you might need to ask a developer to add an ARIA label attribute to make it accessible to screen readers.

While creating accessible content for your blind or vision-impaired visitors, keep in mind that search engines can’t see either. Search engines rely on crawler bots to scan pages for relevant information to make ranking decisions. So, correctly formatted links are also good for your site’s SEO.

Other factors to make your web pages more accessible

As mentioned in the links section above, assistive technologies such as screen readers let users scan a page to find the elements of interest to them and help them make navigation choices. As well as links, correctly formatted headings, buttons and form fields are a crucial to making your site’s pages accessible.

Web headings for information architecture, not graphic design

While tagged heading use had been increasing since the survey began, this year’s WebAIM Million found a 4% decrease in the past 12 months. This reversed trend is concerning because headings are the main way screen readers navigate web content.

If you don’t already pay attention to correct heading structure on your pages, it is another small change that can make a big difference to the user experience.

It is also helps search engines understand what a page is about. So, understanding the purpose of heading tags will make your site more accessible while building its SEO muscle.

When setting up headings throughout your web pages, don’t rely on styling such as bold and different font sizes. Proper heading structure is marked in HTML with an ‘H tag’. These tags are numbered from 1 to 6 and must be used in sequential order if they are to be effective.

If you use a block editor, such as in WordPress, pay attention to the style you choose for text modules.

Choose the Heading 1 for your main page heading. The H1 usually contains the focus keyword for the page, indicating the main topic and purpose of the page for screen readers and search engines. Each page of your site should have only one H1 heading.

Choose the Heading 2 as your subheading, using it to further explain the page’s purpose. Ideally, each page should also have only one H2 heading.

After setting the H1 and H2, you can use as many of the others as you need to help your content make sense. You don’t need to use every heading level. Just remember to use them sequentially so they’re useful to screen readers.

This means, for example, you should not use an H4 heading if you have not already used an H3. Heading hierarchy needs to correspond with the content hierarchy. W3C has detailed information to help you better understand heading tags.

Buttons and form labels with purpose

The WebAIM Million found 48.6% of form inputs across surveyed pages were missing labels. It also found 28.2% had empty buttons.

As with links, button and form field wording should ensure every user knows what they are for and what to do with them.

The wording of buttons needs to convey their purpose. Best practice wording for buttons suggests using verbs and action words to help people commit to a choice. Imagine the button description appearing on a list. Is the wording concise, distinctive and task-specific?

Sometimes links are styled to look like buttons. While they might look similar, the functionality is different. Basically, if an element allows a user to submit an action, it is a true button. If it takes the user to another web page, it is a link.

Forms on your site must have a clear labels, and input descriptions outside each field. Lighter text within a field sometimes describes its purpose. The user’s entry overwrites this text. Problems arise if users lose their place and forget what the field was for.

If your site’s format does not allow the easy addition of descriptions and labels to your buttons and forms, it might be one for your web developer. This is another case where ARIA labels might be useful. ARIA labels are pieces of code visible only to assistive technology, such as screen readers, that explain the purpose of an element where plain HTML is not sufficient.

Keep in mind that ARIA labels are a last resort, as too many can add to complexity errors and interfere with accessibility.

Improve content processes for better web accessibility

Each year, the WebAIM Million report shows slight improvements in content accessibility, with the government and education sectors doing best. But these gains could be far greater if more people made regular small changes to their everyday content processes.

- Add alt text to each new image you upload.

- Use correct heading structure on your new pages and blog posts.

- Check that your colour combinations meet accessibility guidelines.

- Make sure links describe where they lead.

- Label form fields and button.

If you have a bit more time and interest, do W3C’s Digital Accessibility Foundations free introductory course.